What happened to long-term thinking?

During the days of looming global pandemic, I find myself increasingly returning to a topic which I have oft pondered – whatever happened to the future?

Now to be sure it is framed in rather a whimsical way, but at the core resides an age old sentiment about risk that seems now more pertinent than ever.

Human beings have always tried to glean insight about the future and its risks, placing in it’s uncertain care our hopes, dreams, and aspirations. Oracular traditions throughout history have sought to fill this deep seated need – with apocryphal outcome. In a more modern context investors of all stripes spend their days attempting to peer into that receding horizon hoping to divine some key insight with which to guide their high-stakes decision making. But despite all this, the future is never certain, and while history seems obvious in hindsight, the moment to moment experience is never so clear.

The question of thinking about long term benefit comes in part from having once heard the claim that different languages cause different attitudes towards the future, specifically whether a language has a future tense or not, such as English vs German, and what differences this makes in economic saving behaviour.

True or not (and considering it’s a behavioural economics question I’m not holding my breath), it’s likely that this would be far more to do with culture than simply language. One thing that can’t be the case is some recent change in human beings or human nature – no different now than 2000+ years ago.

Some will say ‘why are you overthinking all this future risk business? It’s nothing but irrational panic and hysteria,’ but those people are (often overeducated) fools. Anything with risk of ruin has to be treated with the utmost seriousness. Even if there is only a tiny chance of catastrophe, over a long enough time series – extraordinary events will always blow up.

In short, the paranoid survive. There is an evolutionary bias towards paranoia, as false positives are always less dangerous than false negatives (e.g. thinking a plant is poisonous when it isn’t, is always safer than thinking a plant isn’t poisonous when it is). Now we cannot live in perpetual existential dread either, the negative tradeoff of paranoia if left unchecked, it gets in the way of doing anything.

The trouble is, most people in this safe comfortable modern world of abundance don’t know or think much about risk. We are more divorced from life or death struggle than ever before. Like a young child crossing a quiet street, this naivety creates even greater risk. Knowledge of history can do some good towards alleviating the problem of our own ignorance and complacency,however as the saying goes ‘history doesn’t repeats itself but it often rhymes’. There is a difference between experience gained from a well-seasoned lifetime, and knowledge of once in a century, once in a millennia, etc. probability events.

(Not to mention how common supposedly ‘uncommon’ events actually are.)

How much you can draw relevant lessons in our unprecedented epoch of progress is open to debate. For as much as I am a fan of history, and for as much wisdom you can glean from it – ‘If the past by bringing surprises, did not resemble the past previous to it, then why should our future resemble our current past?’

Increasingly it seems many people never seriously think much about the future at all, and if they do it’s either a shallow expectation that things will change technologically while somehow staying the same, or a doomed resignation to an apocalyptic future. Either extreme is not helpful even if containing grains of sense, both lacking prompt to taking effective action.

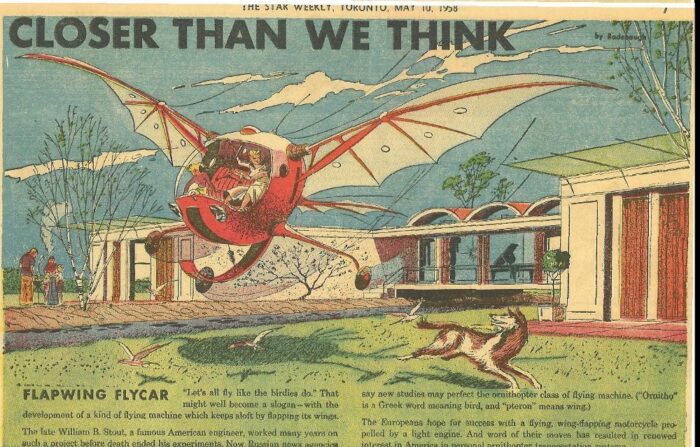

In the case of the former sentiment – Retrofuturism is often fascinating to look back at, and the most telling example when it comes to ‘same-but-different’ expectations of the future. Where are the data tapes, video phone booths, and nuclear cars etc? (By contrast the especially interesting and inconspicuous cases are when the fiction actually got it right).

If you had asked a message boy 1000 years ago what you could give him to make his job easier, he would have said something like a ‘faster horse’, the kind of personal communication tools we have now beyond his wildest imagination. The boy’s limited outlook not being anything unusual, in part due to the often accidental way we make discoveries and the butterfly effect of progress.

In the latter sentiment’s case, pessimism is often more informed or historically reasoned, as collapses have always occurred – from the Bronze Age, to the Roman Empire, ‘Dark Ages’, and beyond. The people then, as now, having the typical human arrogance that it ‘could never happen to us’. What’s new is a desensitisation to the idea by media, such that the possibility seems like mere ‘science fiction’ rather than any kind of plausible reality. In truth human ‘civilisation’ sometimes goes backward, as the examples like the fall of the western Roman Empire demonstrate.

You may think we have progressed past such things, but in most ways we are more vulnerable than ever. We exist in a complex interlink of systems increasingly concerned with efficiency, but simultaneously made fragile, an under-appreciated factor that poses large risk of collapse when things go wrong. Technology is a double-edged sword. Never before have human beings possessed the power to destroy the world, and this capability is only accelerating in variety.

We all know about the threat of nuclear annihilation, but often forget the potential remains great as it ever was, the relatively recent exchanges between Trump and North Korea serving for some a sharp reminder. Most people don’t even know how often and how close we have come to total nuclear war. There have been at least 11 near misses since the 1950s, often due to mere faulty early warning sensors.

This brings us to the first cultural factor for consideration about the end of the future. What does the threat of imminent doom do to society when it hangs so consciously overhead, dripping with possibility?

While it’s always true an asteroid could fall on us at any time, the Cold War from 1949 onwards provided a palpable sense of potential Armageddon unparalleled in history. At what point does the future cease to matter when it could all end at any moment? The hedonism of the 1960’s to the nihilism of today is a trend influenced in part by that grim spectre, because when living in such a shadow – why not live like there’s no tomorrow?

Not to be overly critical of ‘living in the present moment,’ (desire being a contract you make with yourself to be unhappy until you get what you want and all that) but like most things it is a balance.

The future involves sacrifice, sacrifice of the present, and such self-deprival is likely considered unfashionable. Now I’m not suggesting we collectively live for nothing but the future, but if the needle is on a dial that reads past, present, future, we would better served tweaking that needle a bit further in the future direction.

So comes another cultural factor potentially eroding the foundations of concern for the future – the weakening of the family unit and wider social fabric. One contributing development is the contraceptive pill in 1960, a technology of the sexual revolution which we still don’t know the full long-term ramifications of. Individuals should be free to do as they choose, but the children are the ones that always suffer from poor decision making. For a start we know the increase in fatherless homes is one of the single biggest contributing factors to long-term negative outcomes. But when it comes to children, we are an increasingly isolating, self-focused, casual hookup, and even anti-natalist culture. Young people today often never have any relationships at all, let alone long-term ones, or want to have children. With no children there’s no skin-in-the-game of the continuation of humanity, so why care what happens beyond your own lifetime?

(That all said, it is most effective to look yourself in the mirror and start at a scale of one when trying to do something, so long as one doesn’t become solipsistic.)

Turning to a trend stretching even further back into history, another factor to consider could be to do with industrialisation shifting most of us away from agriculture. The development of industry freeing up time and labour is to be commended, but it does have the byproduct of separating most of us from a practical existential relationship with the seasons. Obviously in the grand scheme of things we are just as dependent on this as ever, but it is indirect enough now for most of us that we need never consider it. (Without mentioning how the food supply is vulnerable to the climate changing, as it always has been.)

One of the other consequences of industrialisation is of course the huge demographic trends with influx towards cities, and subsequent decrease in property ownership. Keep in mind concentration brings fragility, and cities always need to get food from somewhere – distribution issues prove just as big a problem in these cases as supply shortages. All of which mentioned comes to a head with the issue of today’s on-demand convenience consumer culture, very efficient, but having little in the way of built-in redundancy. This is why growing food is a great hobby, one that can never be recommended enough, both for decentralisation, disaster preparation, and because the experience of growing something is one we should all have.

But of all the possible end game scenarios, pandemics are the greatest/most likely of all the threats.

In our globalised society fundamental mathematical power laws dictate that which multiplies will have a greater and greater winner-take-all effect. The increasing connectivity and population density allows for easier and easier spread. Natural mutation of viruses and second waves etc. (like the Spanish Flu) are one thing, but the real danger we face is the technology of synthetic biology, with the ability to make biological super weapons. If we follow a simple rate of technological progression, (such as compared with computers, which initially only governments could afford) then eventually anyone will be able to ‘3D print’ a super virus in their basement. This in part is why COVID-19 looks to be a test for us, one that we should learn as much as possible from.

We all know in this interconnected world that we need to be cleaner, remote work is easier than ever and potentially more efficient. The problem is that the scale of interactions continues to accelerate past the level that we find intuitive, which is why the unlikely systemic events that bring risk of common ruin to all must be treated with utmost seriousness. Roll the dice long enough and you will always hit a failure point.

This is why the idea (for example) that humans may never again use nuclear weapons after the past ~80 years seems implausible, and that cultural shifts around increased physical distancing, reducing public crowds/gatherings/protests, avoiding handshakes etc. are all necessary.

This brings us to a point on rates of change, which many feel is already at a level that escapes any individuals ability to keep up. We all have conceptual difficulty with time spans longer than a single human life, but now there is a novel amount of novelty, with so much happening at once. We forget that the onset of obsolete elders is a modern phenomenon, whereas for most of recent human history if you knew, say how to hoe well, that wasn’t a skill going out of fashion any time soon. This is why the timeless is so valuable, just as basic elements about human beings aren’t going to change overnight.

One could also make the argument that, outside of computers and telecommunication, much of the economic growth has been fake for the past 50 years.

When it comes to the question of the future, saying ‘we don’t know’ is the correct answer, but uncertainty is less foreboding than it may seem. As hard as it may be plan long-term without being able to imagine the life of our children, let alone our children’s children, because the future is unknown that actually tells us a lot about what to do now and in some more important ways what not to do. From simple evolutionary reasoning we know that the fragile things will break which is why, to use a Talebian phrase, filtering Via Negativa (by removal) is a better prediction heuristic than the alternative.

Morality itself could be considered in terms of behaviour what is most effective over a long term of reciprocative relationships.

A potential trap of evolutionary reasoning can involve senescence – where sometimes there’s an evolutionary tradeoff in favour of a trait which is beneficial in the short-term, but is negative in the long-term (and when generalised – arguably like fake economic growth).

Back to pandemics, the short term is going to be painful, a stress test not only in on health but on infrastructure as well. Doing what we can to spread out the impact will make a difference e.g. compare being crushed by a boulder to being pelted with a boulders worth of gravel over a period of time.

With COVID-19 there’s still a lot we don’t know. At the current stage, while very bad, thankfully it’s not worse, but this is subject to change, especially in the slight of potential mutations/second waves. The major impact, we should hope, will be economic and cultural. Recession is certain with cascading tolls on production, trade, and finance having long lasting effects on global supply chains. But it’s not all negative, you could throw a sizeable proportion of the workforce out and nothing would happen. The creative destruction could even be beneficial in the long run.

But the big picture overlooks each and every person that will suffer and die because of this disease. We shouldn’t.

To reiterate – best case scenario, bad case scenario, and worse case scenario, these aren’t weighted the same and can’t be treated the same. Scale and time always matter. We must always come down hard on multiplicative and systemic risks. If you can’t predict – prepare. Hope for the best but expect the worst, because you rarely think much about the bad things that didn’t happen.

Despite what psychologists and economists et al. will tell you there is a difference between panic and your instincts treating matters with the seriousness they deserve.

Despair is the enemy, panic is the enemy, cynicism is a way for smart people to signal to each other about how clever they are. Panic can be worse than disease, but lack of panic can be even worse – if enough people act like nothing is the matter it can cause the problem by scale transformation that they don’t think they have to worry about. Early panic is better than late panic, and we should always be humble about what we still don’t know.

Use common sense, don’t let anyone tell you otherwise, you are smarter than a virus. The best thing is for us all to take responsibility, be clearheaded about what matters, and solve our way out of these problems. Tomorrow is promised to nobody.